The Hungarian Constitutional Court has been packed with judges supportive of the governing majority’s agenda. Through appointing new judges, amending rules and increasing the size of the court, the ruling Fidesz government has succeeded in shaping the Constitutional Court into a loyal body, as opposed to the independent and genuine counterbalance to government power it used to represent.

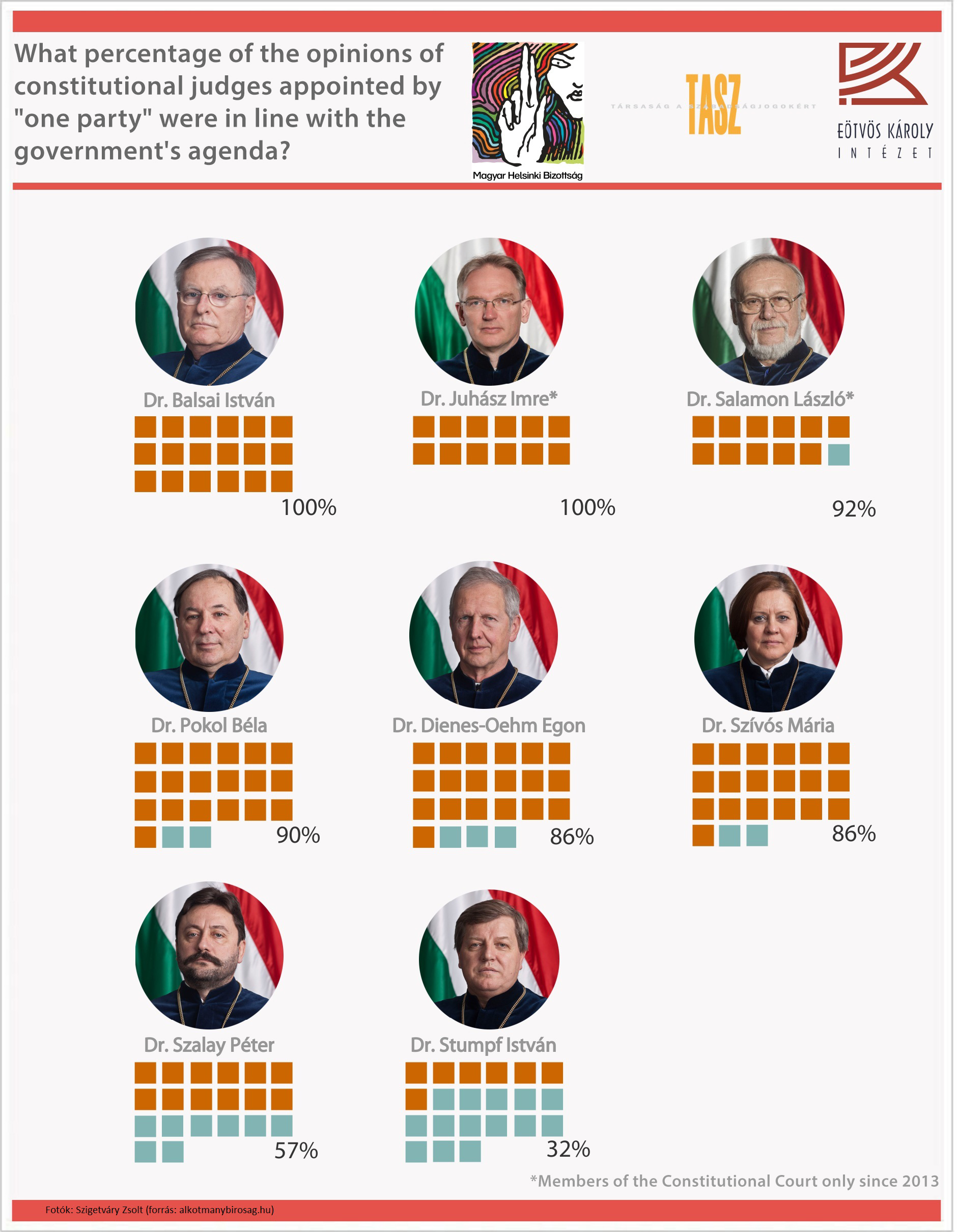

Three Hungarian NGOs - Eötvös Károly Policy Institute, The Hungarian Helsinki Committee and The Hungarian Civil Liberties Union - studied 23 high-profile cases, 10 of which were decided before Fidesz-appointed judges constituted a majority, and 13 after. While rulings in all 10 cases decided before the judges selected by the current government formed a majority had been contrary to the interests of the government, as soon as the ’one-party’ judges represented the majority, the imbalance became apparent: in 10 out of 13 cases the ruling favored the government’s interests.

Some judges were found to have voted in support of the government in 100 percent of cases. Judges Egon Dienes-Oehm, Béla Pokol and Mária Szívós almost always decided in favor of the supposed interests of the government even before the new judges came to form a majority.

So how has the Hungarian Constitutional Court ended up like this? The two-thirds majority in parliament amended the legislation on the composition of the Constitutional Court in three ways:

- Previously, according to the rules of appointment, the governing majority could appoint constitutional judges only together with the opposition. However, this rule was amended in 2010 to allow the majority to appoint new members on its own.

- In 2011, the number of judges on the court was increased from 11 to 15.

- In 2012 and 2013, the judicial terms was increased from 9 to 12 years, followed by the elimination of the age limit (70 years).

As a consequence of all this, 11 of the 15 judges have been confirmed to the court by the Fidesz-KDNP (Christian Democratic People’s Party) majority without any negotiations with the opposition.

Apart from the results discussed above, the study contains profiles of the individual judges. Apart from the results discussed above, the study contains profiles of the individual judges, assessing their opinions on the judicial process and its relationship to democracy, elections, democratic debates, the separation of power and the safeguards of independence. The analyses present in detail the features of decision making characteristic of each judge. Summary tables also support the better understanding of the cases under examination and the judicial practice of judges.

An executive summary of the study is available here in English.

The full study is available here in Hungarian.